"What Is Hateful To You

Do Not Do To Your Neighbor."

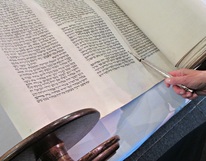

Shavuot is nearly upon us. It is a time when we commemorate both the giving and receiving of the Commandments at Mt. Sinai. It has always been confusing to me why its observance among certain segments of the Jewish community view this as a marginalized holiday. After all, the 10 Commandments not only concretize the Jewish people’s covenantal relationship with God for all time, but give us substantive direction about our role in the world, what we are supposed to be doing with the time we have, and what moves us ideologically, not politically. What is our definition of kindness, how do we relate to God, what is expected of us as we reach out to God? What is expected of us as we relate to other human beings? What is the cornerstone of being a Jew? These seem like questions which beckon us to learn endlessly all the days of our lives, (a good thing), to study Torah, Talmud, the minutiae of commentary, legal codes—but, really, all of Judaism is encompassed in a single statement made by Rabbi Hillel, a leading rabbi of the of 1st century BCE.

The story is recorded in the Talmud. A non-Jew approaches Rabbi Shammai, another leading rabbi and contemporary of Rabbi Hillel, and asks him to teach him the entire Torah while standing on one foot. Shammai, incensed at the man’s impudence, chased him away. The man then approached Hillel, and asked him the same question. Hillel responded, “What is hateful to you, do not do to your neighbor. This is the whole Torah; all the rest is commentary. Go and learn it.”

There is nothing dismissive about Rabbi Hillel’s statement. It encompasses in seemingly simple word and deed what drives the Commandments and the ideology supporting them. They instruct us how to behave, and how not to behave, how to be in relationship with our fellow human beings and with God and how not to be. They embody an essence implicitly charging us to be a light unto the nations commanding us to act with kindness toward others not only because that is how each of us want to be treated but because by doing so, we bring God’s presence into the world. In essence, we are commanded to be kind.

The Commandments are our roadmap, our guide. After all, life is often lived in the gray area. Nothing is black and white. It would be so easy to rationalize our behavior all of the time, but the Mitzvot come to remind us there are certain standards of human behavior. We are not allowed to murder, to kidnap, to covet. We are not allowed to worship anything other than God—not power, not money, not our leaders, not our celebrities, not even ourselves.

The Commandments are our roadmap, our guide. After all, life is often lived in the gray area. Nothing is black and white. It would be so easy to rationalize our behavior all of the time, but the Mitzvot come to remind us there are certain standards of human behavior. We are not allowed to murder, to kidnap, to covet. We are not allowed to worship anything other than God—not power, not money, not our leaders, not our celebrities, not even ourselves.

|

God commands us to pursue justice, acts of righteousness, (Deuteronomy 16:20), and 36 times in the Torah, to be kind to the stranger because we were once strangers in a strange land. In other words, we are commanded to be kind, to engage in behavior which unites us, not to exploit differences for our own personal gain because of color of skin, religion, age, national origin, handicaps, gender or sexual preference.

|

As humans, we are so prone to becoming conditioned to ever changing standards. If we hear politicians engage in bigoted statements, we may come to expect such behavior as part of the political playground. The history of the world is replete with where such sentiments lead and among its victims, we as Jews and as bigotry’s victims carry that knowledge within our historical DNA. Bigotry is never acceptable, not within political discourse, not within governance, not within financial enterprise, not in our personal relationships—not ever. Not ever.

Governing, governmental and community service not so long ago, were viewed as ennobling endeavors. Our cultural sensibilities have much to do with our outlook, how we view ourselves and our purpose in the world. They set a tone of what is acceptable and what is not. We are reminded of President Kennedy’s call to citizens: Ask not what your country can do for you but what you can do for your country. A President Jed Bartlett of The West Wing elevated our view of governance characterized in all its complexity with a sense of integrity and kindness. Now, with gridlock in Washington and so much corruption, it’s difficult to know which leaders to trust anymore. We may find ourselves asking this question: Are our political leaders motivated to provide benevolent service to our country or are they engaged in egocentric visions only promoting themselves? So in today’s political climate we may experience greater understanding with a political culture which produces a President like Francis Underwood as depicted in House of Cards, underscoring the corruption that power often creates, a complete and utter perversion of President Kennedy’s statement.

We understand how dirty political rhetoric may be. We expect this. We understand that some of us have more conservative or liberal views of how our country should function. In the marketplace of ideas this is good. After all, reasonable minds can disagree and from a diversity of competing ideas, innovation and compromise may result.

Governing, governmental and community service not so long ago, were viewed as ennobling endeavors. Our cultural sensibilities have much to do with our outlook, how we view ourselves and our purpose in the world. They set a tone of what is acceptable and what is not. We are reminded of President Kennedy’s call to citizens: Ask not what your country can do for you but what you can do for your country. A President Jed Bartlett of The West Wing elevated our view of governance characterized in all its complexity with a sense of integrity and kindness. Now, with gridlock in Washington and so much corruption, it’s difficult to know which leaders to trust anymore. We may find ourselves asking this question: Are our political leaders motivated to provide benevolent service to our country or are they engaged in egocentric visions only promoting themselves? So in today’s political climate we may experience greater understanding with a political culture which produces a President like Francis Underwood as depicted in House of Cards, underscoring the corruption that power often creates, a complete and utter perversion of President Kennedy’s statement.

We understand how dirty political rhetoric may be. We expect this. We understand that some of us have more conservative or liberal views of how our country should function. In the marketplace of ideas this is good. After all, reasonable minds can disagree and from a diversity of competing ideas, innovation and compromise may result.

|

|

We are a nation of immigrants, a literal huddle of diverse peoples with diverse cultures from all over the world, often persecuted refugees coming together to form one united nation. Herein is found our steadfast resilience and drive to remain a free and democratic nation. The words written by Emma Lazurus and etched into the Statue of Liberty are not merely rhetoric; they are both the cornerstone of America and of our Biblical understanding of the way the world must always strive to become, a beacon of freedom unto the world.

Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free…. |

Politics is politics and bigotry is bigotry. The two are never the same, and never should be conjoined, never. For months now, we have been subjected to bigoted trash talk and there isn’t any one among us, including all of our politicians, who should somehow rationalize and find ways to accept such sentiments. They should be publically and categorically excoriated and rejected. They are un-American, violative of Judaism and of the very fundamental principles of decency.

Shavuot is a time of reflection, a time to be humbled by our relationship with God and with others. It is a time to be grateful for what it means to be a Jew and all the good we stand for in our often misguided world. It reminds us to be more than gracious, but to actually engage in acts of kindness by helping others, by focusing on what unites us rather than what divides us and by doing so, we each become a beacon of God’s light unto the world.